Sistemas de ED lineales de primer orden

Un sistema de ED de primer orden de la forma normal

\[\begin{split}

\begin{aligned}

\frac{\mathrm{d}x_{1}}{\mathrm{d}t} &= g_{1}\left( t,x_{1},x_{2},\dots,x_{n} \right), \\

\frac{\mathrm{d}x_{2}}{\mathrm{d}t} &= g_{2}\left( t,x_{1},x_{2},\dots,x_{n} \right), \\

\vdots \quad &= \qquad \vdots \\

\frac{\mathrm{d}x_{n}}{\mathrm{d}t} &= g_{n}\left( t,x_{1},x_{2},\dots,x_{n} \right),

\end{aligned}

\end{split}\]

se llama sistema de primer orden .

Cuando las funciones \(g_{1},g_{2},\dots,g_{n}\) son lineales en las variables dependientes \(x_{1},x_{2},\dots,x_{n}\) se obtiene la forma normal de un sistema de ecuaciones lineales de primer orden de la forma

(45) \[\begin{split}

\begin{aligned}

\frac{\mathrm{d}x_{1}}{\mathrm{d}t} &= a_{11}x_{1}(t) + a_{12}x_{2}(t) + \cdots + a_{1n}x_{n}(t) + f_{1}(t), \\

\frac{\mathrm{d}x_{2}}{\mathrm{d}t} &= a_{21}x_{1}(t) + a_{22}x_{2}(t) + \cdots + a_{2n}x_{n}(t) + f_{2}(t), \\

\vdots \quad &= \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \vdots \\

\frac{\mathrm{d}x_{n}}{\mathrm{d}t} &= a_{n1}x_{1}(t) + a_{n2}x_{2}(t) + \cdots + a_{nn}x_{n}(t) + f_{n}(t). \\

\end{aligned}

\end{split}\]

Cuando \(f_{i}(t) = 0\) , para \(i=1,2,\dots,n\) , se dice que el sistema lineal (45) es homogéneo ; en caso contrario es no homogéneo .

Si definimos las siguientes matrices

\[\begin{split}

{\bf X} := \begin{bmatrix} x_{1}(t) \\ x_{2}(t) \\ \vdots \\ x_{n}(t) \end{bmatrix}, \quad {\bf A} := \begin{bmatrix} a_{11} & a_{12} & \cdots & a_{1n} \\ a_{21} & a_{22} & \cdots & a_{2n} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ a_{n1} & a_{n2} & \cdots & a_{nn} \end{bmatrix}, \quad {\bf F} := \begin{bmatrix} f_{1}(t) \\ f_{2}(t) \\ \vdots \\ f_{n}(t) \end{bmatrix},

\end{split}\]

entonces el sistema dado en la Ec. (45) se puede escribir como

\[\begin{split}

\frac{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{d}t} \begin{bmatrix} x_{1} \\ x_{2} \\ \vdots \\ x_{n} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} a_{11} & a_{12} & \cdots & a_{1n} \\ a_{21} & a_{22} & \cdots & a_{2n} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ a_{n1} & a_{n2} & \cdots & a_{nn} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} x_{1} \\ x_{2} \\ \vdots \\ x_{n} \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} f_{1}(t) \\ f_{2}(t) \\ \vdots \\ f_{n}(t) \end{bmatrix},

\end{split}\]

o bien

(46) \[

{\bf X'} = {\bf A}{\bf X} + {\bf F}.

\]

Ejemplo

Escriba los siguientes sistemas en notación matricial

\[\begin{split}

\begin{aligned}

\frac{\mathrm{d}x}{\mathrm{d}t} &= 3x + 4y, \\

\frac{\mathrm{d}y}{\mathrm{d}t} &= 5x - 7y.

\end{aligned}

\end{split}\]

\[\begin{split}

\begin{aligned}

\frac{\mathrm{d}x}{\mathrm{d}t} &= 6x + y + z + t, \\

\frac{\mathrm{d}y}{\mathrm{d}t} &= 8x + 7y - z + 10t, \\

\frac{\mathrm{d}z}{\mathrm{d}t} &= 2x + 9y - z + 6t.

\end{aligned}

\end{split}\]

Definition 10 (Vector solución)

Un vector solución en un intervalo \(I\) está definido como un vector columna

\[\begin{split}

{\bf X} = \begin{bmatrix} x_{1} \\ x_{2} \\ \vdots \\ x_{n} \end{bmatrix},

\end{split}\]

donde los elementos son funciones derivables que satisfacen el sistema (46) en el intervalo.

Para el caso de \(n=2\) , las ecuaciones \(x_{1} = \phi_{1}(t)\) y \(x_{2} = \phi_{2}(t)\) representan una trayectoria en el plano fase (plano \(x_{1}x_{2}\) ).

La solución general de un sistema homogéneo

(47) \[

{\bf X'} = {\bf A}{\bf X},

\]

es

(48) \[\begin{split}

{\bf X} = \begin{bmatrix} k_{1} \\ k_{2} \\ \vdots \\ k_{n} \end{bmatrix}e^{\lambda t} = {\bf K}e^{\lambda t},

\end{split}\]

donde \({\bf K}\) y \(\lambda\) son constantes.

Dado que (48) es un vector solución del sistema lineal homogéneo (47) , entonces

\[

{\bf X'} = {\bf A}{\bf K}e^{\lambda t},

\]

\[

{\bf K}\lambda e^{\lambda t} = {\bf A}{\bf K}e^{\lambda t}.

\]

Dividiendo ambos lados por el término \(e^{\lambda t}\) y realizando manipulaciones algebráicas se tiene

\[\begin{split}

\begin{aligned}

{\bf A}{\bf K} &= \lambda {\bf K}, \\

{\bf A}{\bf K} - \lambda {\bf K} &= 0.

\end{aligned}

\end{split}\]

Dado que \({\bf A}\) es una matriz de \(n\times n\) , entonces

\[

{\bf K} = {\bf I}{\bf K}.

\]

Por consiguiente

(49) \[

\left( {\bf A} - \lambda {\bf I} \right){\bf K} = 0.

\]

La solución \({\bf X}\) del sistema (47) depende de un vector no trivial \({\bf K}\) que satisfaga (49) . Por lo tanto, se debe considerar la siguiente ecuación característica de \({\bf A}\)

(50) \[

\text{det}\left( {\bf A} - \lambda {\bf I} \right) = 0,

\]

donde la solución de (50) son los eigenvalores de \({\bf A}\) .

Atención

Una solución \({\bf K} \neq 0\) se llama eigenvector de \({\bf A}\) y corresponde a un eigenvalor \(\lambda\) .

Entonces la solución del sistema homogéno (47) está dada por la siguiente expresión

\[

{\bf X} = {\bf K}e^{\lambda t}.

\]

Theorem 9 (Solución general de sistemas homogéneos)

Sean \(\lambda_{1},\lambda_{2},\dots,\lambda_{n}~\) \(n\) eigenvalores reales y diferentes de la matriz de coeficientes \({\bf A}\) y \({\bf K_{1}},{\bf K_{2}},\dots,{\bf K_{n}}\) sus eigenvalores correspondientes, entonces la solución general en el intervalo \((-\infty,\infty)\) está dada por

\[

{\bf X} = c_{1}{\bf K_{1}}e^{\lambda_{1}t} + c_{2}{\bf K_{2}}e^{\lambda_{2}t} + \cdots + c_{n}{\bf K_{n}}e^{\lambda_{n}t}.

\]

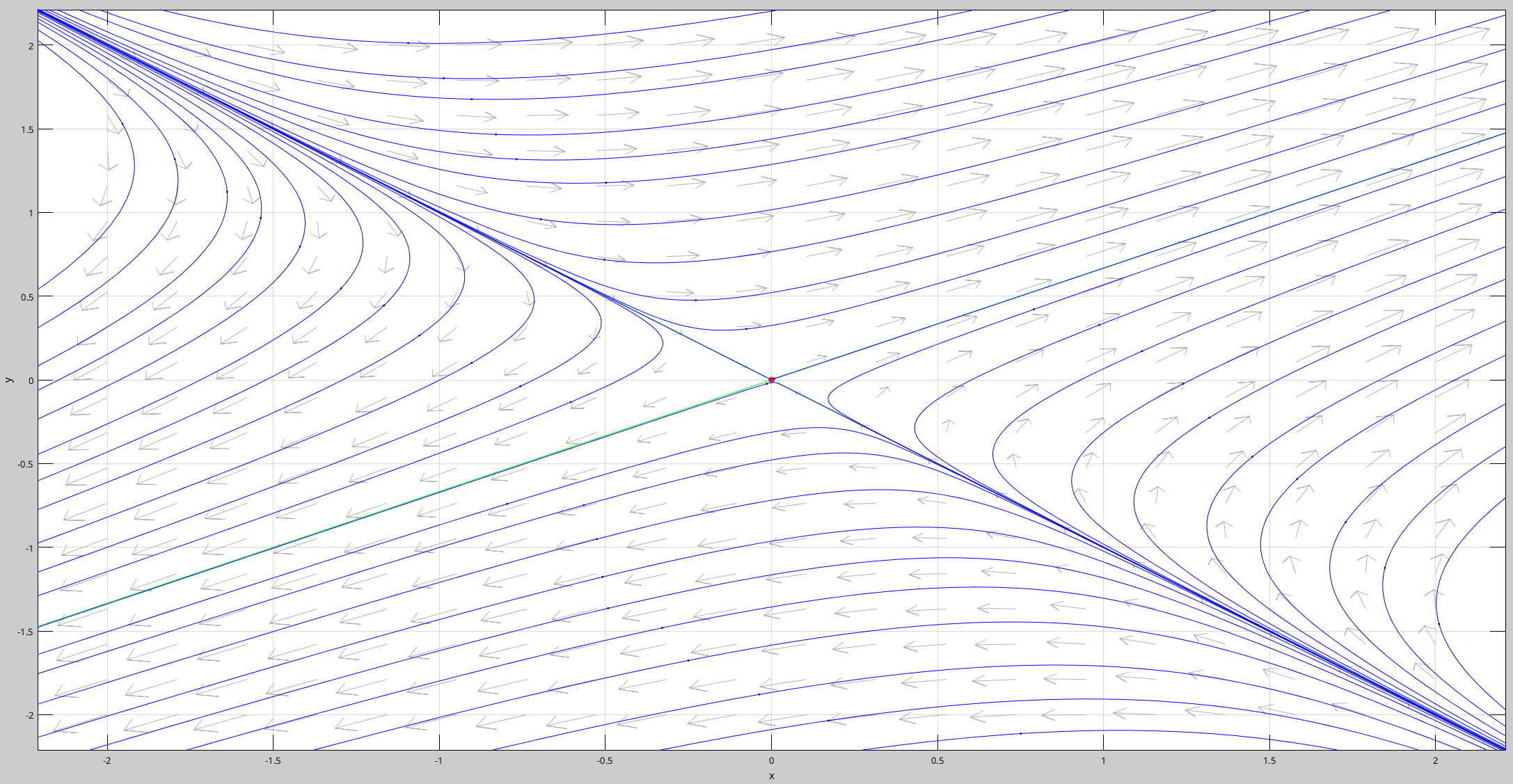

Diagramas de fase

Al conjunto de trayectorias en el plano fase como se muestra en la Figura 1 diagrama fase .

Figura 1 Diagrama fase del sistema péndulo simple.

Aquí se puede visualizar cada eigenvector como un vector bidimensional a lo largo de una de estas curvas.

Importante

El origen se le llama repulsor cuando \(\lambda_{1}>0,\lambda_{2}>0\) y atractor cuando \(\lambda_{1}<0,\lambda_{2}<0\) .

Ejemplo

Determine los eigenvalores y eigenvectores de los siguientes sistemas:

\[\begin{split}

\begin{aligned}

\frac{\mathrm{d}x}{\mathrm{d}t} &= 2x + 3y, \\

\frac{\mathrm{d}y}{\mathrm{d}t} &= 2x + y. \\

\end{aligned}

\end{split}\]

\[\begin{split}

\begin{aligned}

\frac{\mathrm{d}x}{\mathrm{d}t} &= -4x + y + z, \\

\frac{\mathrm{d}y}{\mathrm{d}t} &= x + 5y - z, \\

\frac{\mathrm{d}z}{\mathrm{d}t} &= y - 3z. \\

\end{aligned}

\end{split}\]

\[\begin{split}

{\bf X'} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & -2 & 2 \\ -2 & 1 & -2 \\ 2 & -2 & 1 \end{bmatrix}{\bf X}.

\end{split}\]

\[\begin{split}

{\bf X'} = \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 1 & 6 \\ 0 & 2 & 5 \\ 0 & 0 & 2 \end{bmatrix}{\bf X}.

\end{split}\]

\[\begin{split}

\begin{aligned}

\frac{\mathrm{d}x}{\mathrm{d}t} &= 6x - y, \\

\frac{\mathrm{d}y}{\mathrm{d}t} &= 5x + 4y. \\

\end{aligned}

\end{split}\]

Theorem 10 (Soluciones correspondientes a un eigenvalor complejo)

Sea \({\bf X}\) una matriz de coeficientes con entradas reales de un sistema homogéneo y \({\bf K_{1}}\) el eigenvector correspondiente al eigenvalor complejo \(\lambda_{1} = \alpha + \beta i\) , con \(\alpha,\beta \in \mathbb{R}\) entonces

\[

{\bf K_{1}}e^{\lambda_{1}t}, \quad {\bf \overline{K}_{1}}e^{\overline{\lambda}_{1}t},

\]

son soluciones del sistema dado en la Ec. (47) .

Demuestre el Theorem 10 utilizando el siguiente PVI

\[\begin{split}

{\bf X'} = \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 8 \\ -1 & -2 \end{bmatrix}{\bf X}, \quad {\bf X}(0) = \begin{bmatrix} 2 \\ -1 \end{bmatrix}.

\end{split}\]